The author pointing out a nymphing fish to M. Laurent Sainsot of the International Ritz Fario Club of Paris, on the River Itchen. (Photo copyright Peter Lapsley)

What's in the book

Apart from over 200 photographs.

Chapter 1 pp 25 to 33

How fish see the dry fly

Most dry flies penetrate the surface film and are taken, preferentially, by

trout as emergers and not as hatched-out duns. This is the reason why the

ordinary angler can hope to, and does, do well using the classic dry fly. It

helps to understand what’s going on – but you don’t have to be either an

invertebrate nerd or a religious nut to succeed. Once you do understand

a bit more of what’s really going on you may well feel a stronger need to

move forward as a hunter of trout on your own terms, following your own

ideas rather than being spoon-fed.

TROUT’S VIEW FROM BELOW, the fly having penetrated the surface, which acts as a mirror reflecting the river bottom.

(Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 2 pp 35 to 45

Emerging Heresies

Here we are reviewing the evidence for the orientation of natural nymphs

as they rise and emerge at the surface – and finding that it is diametrically

opposite to the orientation with which our upstream imitation nymphs

and emergers are tied and fished. If we want to fool fish by giving them

the right GISSO (General Impression of Size, Shape and Orientation),

then we certainly need to use reversed nymphs, at least when presenting

them upstream in the surface film, or in the last inch below it. Ditto

emergers.

Suspender GRHE nymphs facing down stream, and up (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 3 pp 47 to 61

Hatched fly presentation

Our hatched dun imitations face the wrong way whenever the breeze is in

an angler’s face, whether they are fishing upstream or downstream. Did we

really want that to happen? The good old boys had it right in their imitations

of duns and also in their presentation of them. It was the angler’s job to

float the fly. The ‘dry fly revolutionaries’ wanted the fly to float itself by its

modern labour-saving design but it didn’t, they goofed and led the sport

astray in this and other respects, and you can be among the leaders of its

restoration if you enjoy a good rant and join me in this further heresy.

Reversed 'Kiss my Cul' (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 4 pp 63 to 73

How fish eat

The way our tippet tethers the fly and frustrates the trout in his attempts

to eat it is something that many anglers don’t consider, and something

that most angling writers have failed to address. Avoiding drag, generally

recognised as key to not putting fish off the take and causing rejection,

is also crucial, mechanically, in terms of the physics of getting the fly

into the trout’s mouth without it bumping out, hitting bone, or sparking

ejection. Loose tippet is the answer.

Focussed on a floating fly - zero drag! (Photo copyright Don Stazicker)

Chapter 5 pp 75 to 81

Casting every which way – but loose

I hesitate to instruct: I’m neither qualified nor good at it. What I try to

do here is to pass on my own experience for what it is worth, so that the

reader can try out the casting techniques I (and others) use, and see if they

work for you. All I can say is that there is a pretty solid body of conviction

and practice in the sport that uses the same drag-avoiding techniques –

and one which dates from at least as far back as Halford, writing in 1889.

Richard Banbury using the dump cast on a particularly derisive Itchen trout (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 6 pp 83 to 87

How fish see the leader

You actively reduce your chances of hooking trout if you sink your dry fly

leader. I explain how and why, and if you follow my heresy and ensure that

it floats you will find I’m right and catch more fish. And we discuss ways

of approaching fish without scaring them in the light of their incredibly

sharp vision.(Please note, the advice to float your tippet does not apply to

dry fly fishing in still waters or dry fly fishing downstream, i.e. to situations in which

the trout is on the other side of the fly from yourself and focused on the surface).

Fly seen in trout's mirror, tippet sunk (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 7 pp 89 to 97

Whatever floats your fly

This is a review of the development of fly floatants in the past and

recommendations for the present. Here again, quot homines, tot sententiae

– there are as many opinions as there are men to hold them, and everybody

has their favourites. I specify three products that I use for different

purposes and in different situations, each of which has its advantages.

For me, keeping flies made of CdC floating without discolouring them is

very important, as is keeping the leader in the surface film.

Kiss my Cul from above, treated to float (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 8 pp 99 to 109

Experiments outside the box

Other people’s earlier experiments with flies and fish may be anecdotal

in character and often lack the rigour of statistics – yet somehow, given

that they were undertaken by very serious people searching after angling

truths, one has to believe them. There are lessons in all of them for us

today, and I have not flinched from drawing the conclusions. You might

criticise me for this, but in my view ‘you better believe it’. And they are

fascinating.

Vincent Marinaro,A Modern Dry Fly Code (1950),p73 (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 9 pp 111 to 117

Fishing in rivers where you can’t see the fish

If, as I mainly do, you fish rivers that keep their trout from your gaze by

having a dark background or by being turbid, you can still go and learn

from rivers that you can see into and draw on the help of seen fish to give

you guidance on how to fish when the trout, and hence you, are ‘in the

dark’. There are more fish in front of you than you think. This chapter

provides straightforward help with turning unknown unknowns into

known unknowns.

Fifty Shades of Green-- a previously unseen trout rises for the second time on the R. Wylye (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 10 pp 119 to 125

Fishing so the fish can’t see you

This chapter is all about how not to scare fish. It concentrates specifically

on how to avoid scaring fish that are there in front of you but that you

can’t see. As well as examining the general principles of non-scary onstream

behaviour we look at the measures you can take to avoid rod flash

and line flash, and end up addressing the finer points of how the angler

can ‘dress to kill’.

Owain Mealing Fishing unseen by fish (Photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 11 pp 127 to 133

Can we get better fishing than we’ve got?

Most fly fishermen would agree on these three desiderata: more fishable

water; more (wild) fish; and more fly life. Can they have them? The

answer is yes, and in this chapter we look at how to improve the carrying

capacity of a fishery both for fish and for fly. We discuss the importance

of enhancing the sporting character of our fishing by concentrating

where possible on wild fish, and managing our fisheries for their benefit.

We look at physical river restoration, but also at the more radical idea of

biological restoration.

Re-energising the river: the author directs operations (Photo copyright The Wilton Fly Fishing Club)

Chapter 12 pp 135 to 155

Dry flies from outside the box

These 16 flies are the product of a fevered angling mind, and a great

deal of experimentation with trout whose reactions could be seen over a

period of more than 30 years. I didn’t invent them – I just stole the bits.

They are mainly fly designs rather than patterns – they are constructed

to perform in particular ways, on and in the surface, and you can tie

them in any colours and many materials to match the natural flies in the

waters you fish yourself. Basic tying instructions and some hints as to

their use are included, and full instructions for the ‘PhD’, the ‘Muskrax’,

and the ‘Hayestuck’.

Hayestuck, emerger/ cripple (photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 13 pp 157 to 165

Tangential thoughts about nymphing

While I have a lot to say on the construction of dry flies I have very much

less to say on nymphs and nymphing. In contrast to the dry fly, where it

is my view that people have really gone a bit astray over the years, missing

some good opportunities for imitating items that trout want to eat as they see

them, the same is not really true of nymphs. Still, I’ve learned a few tricks,

developed a few very successful patterns, and I’m glad to pass them on.

We look at how nymphs behave in the water, and how they can be managed

to fit in with the expectations and feeding habits of the fish.

Reversed olive nymph (GRHE) to fish in film (photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 14 pp 167 to 175

The evening rise – what evening rise?

I thought it might be helpful to include a chapter on the kinds of strategies

one can use to approach difficult situations – and the evening rise (or the

lack of it) sprang to mind as one of our greatest challenges. So here we

have a look at the reasons why the evening rise is so problematical and

yet so important. Then we cover some practical ways of addressing them.

Spinnermalist (photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 15 pp 177 to 187

Pushing the envelope

This chapter deals with mimicking the hidden secrets of the trout’s

larder. It deals with the imitation of a bunch of little things that don’t look

very nice but which feature heavily in the diet of trout, and can in fact be

tied as flies and presented to the fish successfully, given a certain amount

of application on the part of the angler. Although these little critters are

not always easy to imitate, the results of success can be surprising, and

their use can account for some extremely big fish.

Chapter 16 pp 189 to 195

Imitation’s last frontier

Baetis (olives, that is) can account for as much as four-fifths of your small

upwing f lies, and all of them crawl beneath the surface to lay their eggs

and then float up as exhausted spinners, mostly to stick to the underside

of the surface film. A problem as yet only partly solved – but we review

some creative innovations, each of which gets us closer to a solution.

Plastron-silvered Female Olive (Baetis) egglayer, under water, with eggs. (photo Peter Hayes)

Chapter 17 pp 197 to 203

Playing and netting big trout

Getting to the point where you can confidently play and net big fish is a

steep learning curve with many points at which you can fall off and with

a high risk of disaster attending your efforts to learn. The stakes are high,

and the smaller your experience the scarier it is. So, no pressure then,

as they say. In this chapter we go through the logic of how best to take

away the fish’s advantages and empower your own. It’s the dos and don’ts

really, but it may help to add understanding in terms of the whys.

Keep the fish upstream of you (Photo by Owain Mealing)

Chapter 18 pp 205 to 215

Purism has got us facing the wrong way

The Dry Fly Revolution was initially a technical one, but became a moral

and ethical one when Halford took it over. With his harsh judgmental

light shining on the sport, facts as well as perceptions became twisted

in favour of fishing ‘perfectly dry’ at the peril of not being a gentleman.

The sporting, intuitive, and imitative development of fly fishing was

kidnapped and we still need to escape from the box we got put in. Worse

still, dry flies fished upstream face the wrong way when the wind is in

our face.

When did you last see your father ... use a nymph?

Chapter 19 pp 217 to 235

Reading outside the box

A fresh look at the history of fly fishing before we got put in the box.

From Berners to Halford they all fished floating flies, and fished them

as dry as they could. The past does inform the present. These Ancients

may have worn frock coats and tricorn hats but they were at least as clever

as we are, and much better fly fishermen than we have been allowed

to think. And they fished the dry fly not the wet. It was the hatched fly

they imitated. They wrote well and, if we read carefully, they tell us just

exactly how they fished . With 19th century tackle ‘improvements’

however, their flies got dragged below the surface, and floating your fly

got more difficult in the first half of that century.

John Worlidge on upstream wading,1675

Chapter 20 pp 237 to 243

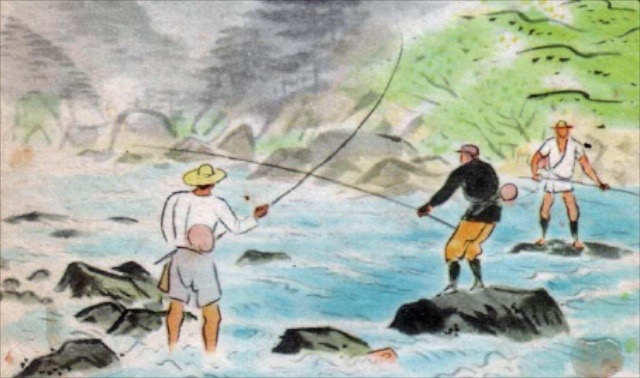

Full circle with Tenkara ?

It is more than a little weird to see the modern, state-of-the-art, UK

fly fishing world being led back in full circle to those only-just-lost

simplicities and skills by this thing called Tenkara that comes to us from

undocumented, oral-tradition Japanese practices via the highly web-documented,

enthusiastic descriptions of new American aficionados. Our

own, much stronger, more highly developed and copiously documented

fly fishing tradition had effectively been suffocated. Nature abhors a

vacuum.

From Angling in Japan, M. Matuzaki, 1940

Chapter 21 pp 245 to 251

A philosophy of fly fishing, from outside the box

Because I take up such a robust position on so many things in fly fishing,

I thought it might help to understand where I am coming from if I tried

to give the reader some insights into my own personal beliefs about life

and fly fishing. But don’t worry, I stick pretty close to fly fishing and I

don’t wander off into any tragedies of personal life or worries about sex,

death and taxes.

Taking a rest, Stephen Beville, Waitangitaona (photo copyright Peter Hayes)

Chapter 22 pp 253 to 256

Caudal Fin

A closing thought or two for fly fishing duffers, middle of the road

anglers and experts alike. Including...

Three philosophers and no rise (photo copyright Peter Hayes)